During the swimming season (around November/December to February/March), regional, unitary, district and city councils, along with public health agencies, monitor and assess the health risks from faecal (‘poo’) contamination at swimming spots across New Zealand. At some river and lake sites, they also check for toxic algae.

LAWA gathers, displays, and updates these monitoring results throughout the day. Authorities issue warnings as needed, so you can see up-to-date water quality information before swimming.

Why can water cause illness?

When water is contaminated by human or animal faeces (‘poo’), it may contain disease-causing microorganisms such as bacteria, viruses and protozoa (for example, salmonella, campylobacter, or giardia). These pathogens can make people sick during water-based activities like swimming. The most common illness is gastroenteritis (stomach upset), but respiratory illnesses, ear infections and skin infections are also possible.

To assess risk, we measure faecal indicator bacteria:

- Enterococci in coastal (marine) waters.

- E. coli in freshwater (rivers and lakes)

The presence of these 'faecal indicators' are used to indicate the levels of disease-causing organisms in the water. For more information, see this factsheet on faecal indicator bacteria.

At some freshwater sites, toxic algae (cyanobacteria) can also be a concern. Toxic algae can grow to high levels (known as toxic algal blooms). Some species of cyanobacteria can produce toxins, but they are not always toxic. For more details, see this factsheet on toxic algae.

What does the summer recreational season monitoring tell us?

For most monitored sites, LAWA shows:

- The most recent water quality result

- Historical data from the past five years

- A long-term grade, based on the five-year data collected during the recreational (bathing) seasons

Together, this information, plus any active warnings, help you decide whether a site is suitable to swim. For more on how to interpret the information, see What do the swim icons mean? and Swim Smart Checklist factsheets.

Weekly sampling & predicted water quality

Faecal indicator bacteria

Most councils sample water quality weekly during the swimming season. The weekly results give a snapshot of the water quality at the time of testing.

However, water quality can change quickly - especially after rain. That is why, even at sites with generally good water quality, we recommend avoiding swimming for 2-3 days after heavy rainfall, since runoff from urban or rural land can affect swimming water quality.

In several regions (Northland, Auckland, Wellington, and Canterbury) water quality is also predicted using models. These predictions are updated frequently to provide a 'real-time' assessment of risk. Some models are simple (using past water quality data and rainfall), while more advanced ones also include tides or stormwater overflows.

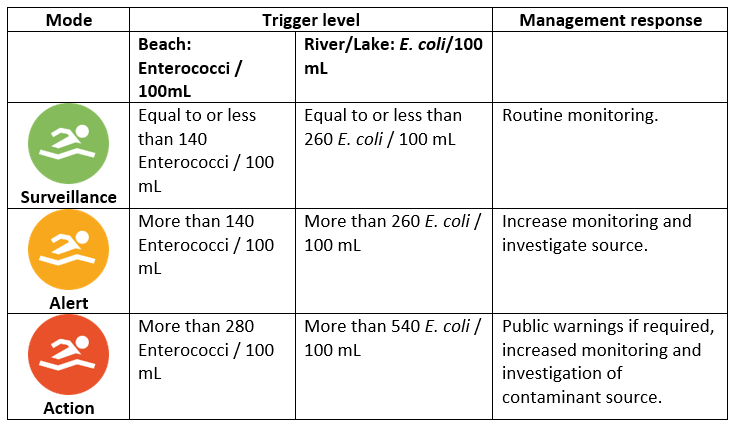

Agencies use use trigger levels defined in national guidelines to evaluate test results and take action when necessary. These guidelines include the 2003 Microbiological Water Quality Guidelines for Marine and Freshwater Recreational Areas and the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (2020).

The trigger levels and corresponding management responses are shown in the table below.

When water quality falls in the ‘Surveillance’ category, it indicates a low risk of illness from swimming. If water quality moves into the ‘Alert’ category, it indicates an increased risk of illness from swimming, though still within an acceptable range. However, if water quality reaches the ‘Action’ category, it poses an unacceptable health risk from swimming.

Note that under the 2003 guidelines, health warnings for coastal waters are only issued after two consecutive samples (within 24 hours) exceeds the ‘action’ trigger level.

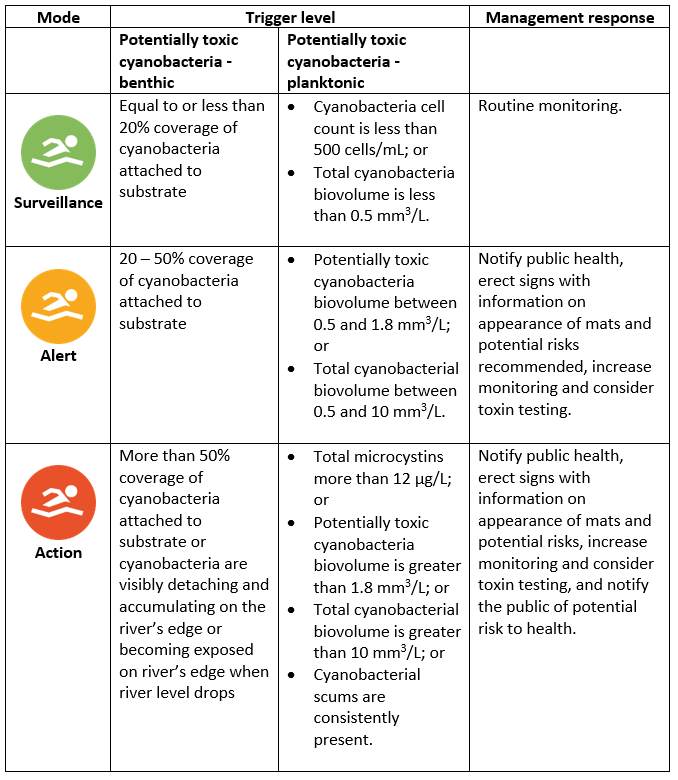

Toxic algae (cyanobacteria)

The risk from cyanobacteria is assessed in different ways depending on the site: by measuring coverage of mats on river beds, by look for mats washed up on river banks, or by measuring concentrations in the water column (especially in lakes or slow-moving waterways).

These measurements are compared to national guideline trigger levels (New Zealand Guidelines for Cyanobacteria in Recreational Fresh Waters: interim guidelines*).

The trigger levels and corresponding management responses are shown in the table below.

*New guidelines, released on 5 December 2024, outline an updated monitoring framework for assessing public health risks from cyanobacteria associated with recreational activities in lakes and rivers. These guidelines will be progressively implemented by agencies responsible for monitoring and reporting on recreational waterways.

Not all recreational sites are monitored for toxic algae. Since it can be harmful, even in small amounts, we recommend learning what it looks like, and avoiding contact when you see it. For more details, see this factsheet on toxic algae.

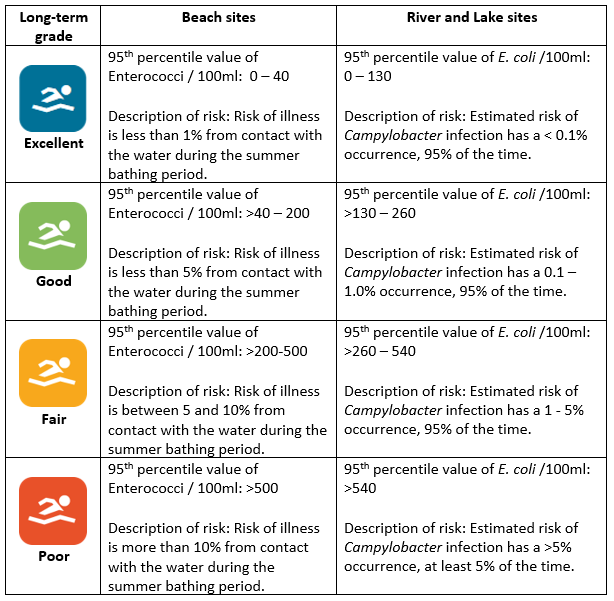

Long-term grade

The long-term grade is a precautionary guide to general water quality, assessing whether a site is Excellent, Good, Fair or Poor for swimming during the recreational bathing season.

This overall grade is risk-based and may not reflect conditions on a particular day.

The grade is based on faecal indicator bacteria data (E. coli for freshwater, enterococci for coastal) over the past five bathing seasons.

The long-term grade aligns with the Microbiological Assessment Category (MAC) in the Microbiological Water Quality Guidelines for Marine and Freshwater Recreational Areas for coastal sites, and the attribute bands (table 22) in the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (2020) for freshwater sites.

What it means in practice?

- Sites graded as Excellent, Good, or Fair typically have suitable water quality for swimming more often than those graded as Poor over the past five bathing seasons.

- 'Poor' doesn't always mean unsuitable for swimming - this category encompasses a range of water quality results, from sites that may only exceed guidelines occasionally, to those with a history of repeated or ongoing exceedances.

- Many popular swimming spots exceed guidelines after adverse weather conditions but are often suitable for swimming outside these times. That’s why we recommend avoiding swimming for 2–3 days following heavy rain, regardless of the recent monitoring result or long-term grade.

- When deciding where to swim, a Poor grade should prompt you to look closer at the data under ‘Why this status?’ on the site page to understand how the swim spot has performed over time.

How is the long-term grade calculated?

The long-term grade on LAWA is based on the Hazen 95th percentile of sample results from the last five recreational bathing seasons. In simple terms, if a site has a 95th percentile of 200, it means that 95 out of 100 times the results were at or below 200 E. coli/100 mL (freshwater sites), or 200 enterococci/100 mL (coastal beaches) when tested.

Notes on the analysis:

- Samples are from the recreational bathing season (last week of October to the end of March).

- Data from the past five recreational bathing seasons (2020/21 to 2024/25) are used to represent weather conditions over several summers.

- Weekly routine sampling results are used. Data from follow-up samples taken in response to elevated results are excluded where councils provide metadata that identify follow-up samples.

- At least 50 sample results over the last five seasons are required, and the site must be part of a recent monitoring programme.

- Sites not routinely monitored in either of the last two bathing seasons (2023/24 and/or 2024/25) are excluded, even if they had at least 50 data points.

- For estuarine sites monitored for both enterococci and E. coli, we apply a precautionary approach by assigning the worst result from the two bacterial indicators.

- Toxic algal data, or other factors such as swift river or tidal flows that might make a site unsuitable for swimming are not included in the grade calculation.

Wet weather effects:

Rain causes runoff that can increase bacteria counts in waterways, and this can lead to higher counts in wet summers. Some councils account for the influence of rainfall by limiting sampling to dry weather conditions when people are more likely to swim. Other councils remove rain-affected bacteria results before calculating the 95th percentile, so the data may better reflect typical swimming conditions.

Health and safety considerations may also restrict when sampling can be undertaken during wet weather.

Because there is no standard national method for adjusting rainfall-related sample data, no adjustments have been made to data presented on LAWA. LAWA uses all routine sample results, regardless of weather conditions, in the long-term grade calculations.

FAQ

What is the impact of rainfall?

Rainfall can significantly affect water quality at river, lake and beach swimming spots due to urban or rural runoff.

- In urban areas rainwater collected from roofs, roads, car parks and other surfaces is piped directly into rivers, streams and coastal waters. Along the way, the stormwater picks up sediment, rubbish, contaminants, and droppings from birds and dogs. Sewer overflows may also occur during wet weather in urban areas.

- In rural areas, excess rainwater flows over the land and into nearby streams and rivers, picking up manure and other contaminants.

- Additionally, heavy rain and wind can churn up sediments in rivers, lakes or estuaries, potentially releasing pathogens trapped in bottom sediments back into the water.

Why can the weekly monitoring result be 'suitable for swimming' when the long-term grade is 'Poor'?

A 'Poor' long-term grade indicates an elevated risk of illness compared to sites with better grades. However, the most recent samples can still show water quality within acceptable limits for swimming. The long-term grade is based on data from the past five bathing seasons, which may include results affected by heavy rainfall, high river flows, or bacteria contamination from storm water run-off or sewer overflows (in both dry and wet weather).

For sites with a 'Poor' grade, you should review the historical data to see if monitoring results frequently exceed guidelines. If exceedances are common, it is best to choose another place to swim.

Some sites may be graded 'Poor' because, while most test results passed, a few exceeded the guidelines - sometimes significantly. For these sites, if the most recent results meet swimming guidelines, the water looks clean and clear, there hasn't been recent heavy rainfall, and no pollution sources are evident, or warnings are posted, it's likely the water quality is still suitable for swimming. For more information about a specific site, contact the council responsible for monitoring.

What other risks are not covered by water quality monitoring?

Swimming at your favourite beach, river, or swimming hole involves safety risks that are not captured by routine water quality monitoring.

Some health risks are not included in regular testing. For example, not all river and lake sites are routinely monitored for toxic algae (cyanobacteria), and algal blooms can develop rapidly between sampling days. Unexpected pollution events can also occur at any time.

Physical hazards may also be present. These include strong river flows or tidal currents, sudden drop-offs, submerged objects, and potentially harmful plants and animals (for example, stinging jellyfish, or organisms that cause swimmer's itch).

In addition, there may be contaminants that are not part of regular testing, such as certain chemicals, heavy metals, or other pathogens.

Before swimming, check local signage, consider recent weather and water conditions, and assess the site for physical hazards. If in doubt, choose another location. More information in our Swim Smart Checklist.

Roles and responsibilities of agencies

Monitoring of recreational water quality involves multiple agencies: regional councils, district and city councils, and public health. The roles and responsibilities can vary in each region but most follow those recommended by the Microbiological Water Quality Guidelines for Marine and Freshwater Recreational Areas.

The regional councils and unitary authorities are responsible for running monitoring programmes, including:

- Weekly sampling at popular swimming sites

- Investigations of sources of contamination

- Informing the Medical Officer of Health (Community and Public Health) and the local district or city council if Alert or Action levels are reached

- Collating information for annual reporting and for grading of sites.

The Medical Officer of Health at Community and Public Health is responsible for:

- Reviewing the effectiveness of the monitoring and reporting strategy

- Ensuring the territorial authority is informed

- Ensuring the territorial authority informs the public of any health risks.

The district or city council is responsible for:

- Informing the public when the Action level is exceeded

- Assisting with identifying sources of contamination

- Implementing steps to abate or remove any sources of contamination.

In addition, under the National Policy Statement for Freshwater Management (2020), regional councils and unitary authorities are required to take practicable steps to notify the public when designated freshwater primary contact sites exceed 540 E. coli per 100 mL during the bathing season.

LAWA brings together up-to-date water quality test results and health warnings from across the country in one easy-to-use place.

Find out more

- Visit the Can I Swim Here? topic for monitoring results and information at recreational swim sites across New Zealand.

- For further information about recreational monitoring programmes in a region or water quality conditions at a specific site, contact the local regional or unitary council.