LAWA Estuary Health - National Picture 2025

Published: 28 September 2025

Why estuaries matter

Healthy estuaries are home to a great number of different plants and animals and have high ecological value. They are important mahinga kai (food gathering) places and provide opportunities for people to connect with nature and each other. Estuaries also play a major role in supporting water quality through natural filtration and binding pollutants within sediment. If we can look after estuaries, they can look after us.

What is monitored and shown on LAWA?

We present information about the estuary monitoring data from New Zealand's regional councils and unitary authorities at a national scale.

Estuary health data have been collated from hundreds of monitoring sites across 104 different estuaries (around one-third of all estuaries in the country). This year, estuaries in Gisborne are included for the first time. The data we report comes from regular sampling as part of State of the Environment monitoring programmes. These data help scientists and decision-makers understand estuary health and track changes over time.

The 442 monitored sites listed on the LAWA website represent a wide variety of estuary types, ranging in size from a few hectares to tens of thousands. Some estuaries have been monitored for one or two years, while others have records from over three decades. LAWA presents data from 2010 onwards, as this marks the most complete and consistent national dataset. The Estuary Health topic focuses on long-term monitoring sites, with data records that will continue to grow over time.

This topic includes results for key indicators of estuary health, currently monitored by regional councils and unitary authorities:

-

Mud content refers to the amount of fine silt and clay particles (collectively known as mud) that are present in the surface layers of estuary intertidal flats. Mud content is a key environmental factor that influences where plants and animals can and cannot live within an estuary.

-

Contaminants include the metals copper (Cu), lead (Pb), zinc (Zn), cadmium (Cd), chromium (Cr), nickel (Ni), silver (Ag), mercury (Hg), arsenic (As), as well as organic contaminants like hydrocarbons and pesticides. When present at high concentrations, these substances can negatively effect estuary health.

-

Estuary macrofauna are small invertebrates visible to the naked eye and include hundreds of species of worms, snails, crustaceans, and shellfish like pipi and cockles. Macrofauna are good indicators of estuary health because the community of invertebrates found in an area reflect long-term, local environmental conditions.

These indicators have been selected for the Estuary Health topic as they provide meaningful insights into estuary condition and are monitored consistently across the country. In some regions, councils also track other useful indicators such as sediment nutrient concentrations, sediment organic matter, chlorophyll a, sedimentation rates, and the extent of certain habitats.

Council estuary monitoring programmes are designed to give insight at a local level, so site selection is often biased towards local monitoring requirements. As a result, caution is advised when comparing the results on a national scale. The number of monitoring sites within each estuary is not necessarily proportional to the estuary's size and may depend on factors such as pollutant levels, resource availability, estuary type, and more.

Estuary health current state

Monitoring data reveal some broad patterns about New Zealand’s estuaries:

-

Estuaries near cities and towns tend to be muddier and more contaminated than those in less modified areas.

-

Metal contaminants are typically found in higher concentrations in estuaries close to cities.

-

High mud content is generally the biggest stressor of estuaries in rural areas.

Estuary health can vary greatly, even within the same region. For example, Waitematā Harbour is surrounded by the country’s largest city, and has elevated concentrations of zinc, lead, and mercury in some areas. Further north in the Auckland region, Whangateau Harbour is surrounded by crops, grassland, and small urban areas and has very low levels of both contaminants and mud.

To give a snapshot of the current condition of monitored estuaries, summary statistics were calculated based on the latest available data for each site, focusing on two indicators: estuary macrofauna score and mud content.

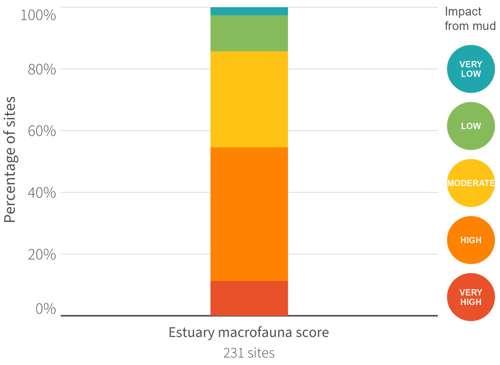

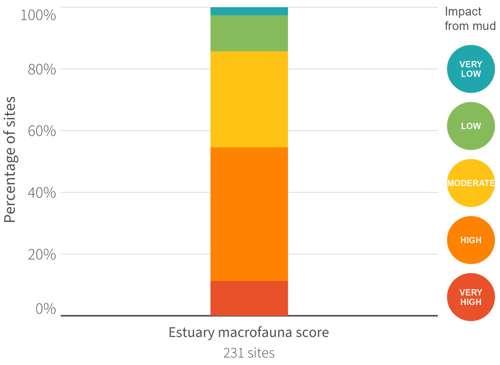

The estuary macrofauna score assesses the health of monitored sites and tells us how relatively impacted the macrofaunal community is by mud, the main stressor of estuaries across the country. According to these scores:

Estuary macrofauna score

Figure 1. The latest estuary macrofauna scores for 231 estuary sites with suitable data available.

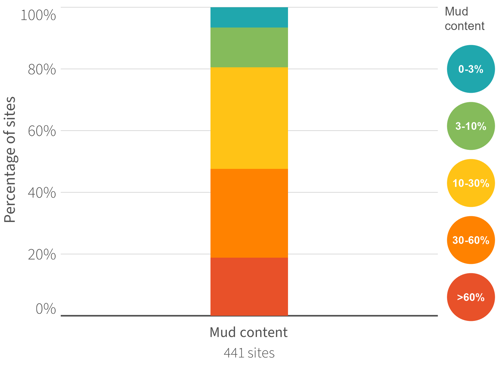

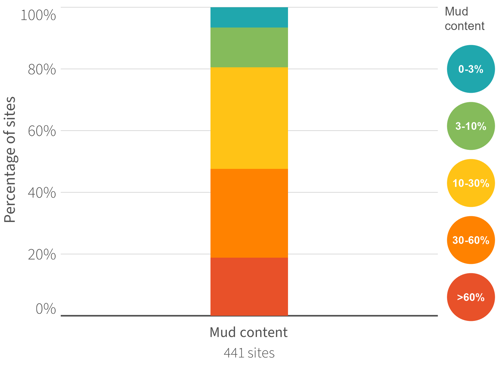

The amount of mud at monitoring sites ranged from 0% to 98.5%. Most sites had concentrations in the 10–30% range, closely followed by those in the 30–60% range (Figure 2).

Mud content

Figure 2. The latest mud content data for 441 estuary sites.

Five contaminants were sampled at more than 80% of estuary sites across the country: copper, lead, zinc, arsenic and mercury. Concentrations of these contaminants were below the Default Guideline Value (DGV) from the Australian and New Zealand guidelines for Fresh and Marine Water Quality (ANZG) at most sites, most of the time. Only 41 sites (approximately 11%) had concentrations of at least one of these contaminants that exceeded the DGV, placing them in the ‘amber’ category, meaning concentrations were high enough to possibly cause ecological impacts. No sites had contaminant levels that triggered the ‘red’ category under the ANZG, where ecological impacts are considered probable.

Estuary health monitoring and reporting

Estuaries are complex ecosystems, influenced by both land-based activities upstream and marine processes offshore. This makes it challenging to identify and manage all the factors that affect their health. Additionally, estuary management is complex as many agencies have overlapping roles, and it is not always clear who is responsible. In many cases, it has taken decades of deforestation, development and land use changes for mud and contaminants to build up, and the estuary type is also a factor in how susceptible an estuary is to the various threats.

Restoring estuaries takes time, and some estuaries may never return to their ‘natural’ state. However, the dynamic nature of estuaries means if we reduce the volume of pollutants entering them, they may have the potential to recover. For example, contaminant lead (Pb) concentrations have decreased in many urban estuaries since the mid-1990s, following the removal of lead from use in paints and petrol.

The Estuary Health topic will be expanded as the collection of data for additional indicators becomes more consistent across the country. Recent and ongoing work by the Ministry for the Environment to stocktake environmental attributes, collate advice on estuary indicators for Aotearoa New Zealand, and revise the National Estuary Monitoring Protocol, will support this growth.

Explore more

You can explore estuary health data through the Estuary Health topic. Use the interactive map (on desktop) to investigate patterns within estuaries and regions, and view indicator graphs to see how values have changed over time.

A range of additional resources is available online through LAWA and our partner organisations to help inform and inspire.

Factsheet: Understanding estuaries

Factsheet: Estuary types

The Department of Conservation’s Estuaries Hub connects people with each other and with resources to help improve estuary health. It offers a wide range of resources developed in partnership with councils, educators, and restoration groups.

Estuary hub

Ministry for the Environment (MfE) and Stats NZ regularly report on the state of Aotearoa New Zealand’s marine environment. Our marine environment 2022 is the latest in a series of environmental reports that includes a national overview of estuary health.

Our Marine Environment 2025

Stats NZ collect information to publish insights and data about New Zealand, including marine indicators that relate to estuary health.

Coastal and estuarine water quality

Heavy metal load in coastal and estuarine sediment